History

I learned to love history from my 5th grade teacher, Mrs. Ashby. She would show us slides of her family’s road trips around the country, which included her as a long-limbed teenager with a goofy grin. I loved her stories, her slides, and her fascination with the Civil War—which I seem to remember stemmed from her father. I still have the copy of John Ransom’s Andersonville Diary that she either gave me or I chose during a prize raffle. I remember being fascinated and appalled by the infinite cruelty of war.

When I was in 8th grade, she came into our classroom again to teach us history. I went to a very small parochial school, so the teachers moved, not the kids. That year, 1990, Ken Burns’ Documentary about the Civil War came out and she showed us several episodes. Reflecting back on this, I wonder if her influence help spark my interest in social justice. The Ken Burns documentary did a decent job of portraying the war fairly with an emphasis on slavery and the role of slaves leading up to and during the conflict. I remember feeling a burning sense of injustice and indignation when they showed pictures of slave’s backs welted with scars and feeling admiration for the eloquent words of Frederick Douglas that seems to have stuck with me.

In college, I got a waiver to take a Civil War History class instead of the required American History class. I loved it. My professor came to class with sabers and charged the screen when a picture of his ex-wife appeared in his slideshow.* I researched women’s role in the war, including women soldiers. For my term paper, I researched Native Americans in the war. I learned a lot. My professor scoffed at me when I told him that I was a Fisheries and Wildlife student when I went to pick up my final paper after the end of the semester. I had gotten a 96/100 and he was disappointed that I wasn’t a history major. Truth be told, if I wasn’t a scientist and educator, I would have been a historian.

After undergrad, I lived in Atlanta for a while. I visited Kennesaw Mountain and Underground Atlanta, where you could still see a cannon shell lodged in a period lamppost. Then I moved to Oregon, which temporarily halted the Civil War sightseeing opportunities. When I knew I would be moving to DC, I got excited at the prospect of visiting more battlefields—many which I’d been wanting to visit since I was in 5th grade.

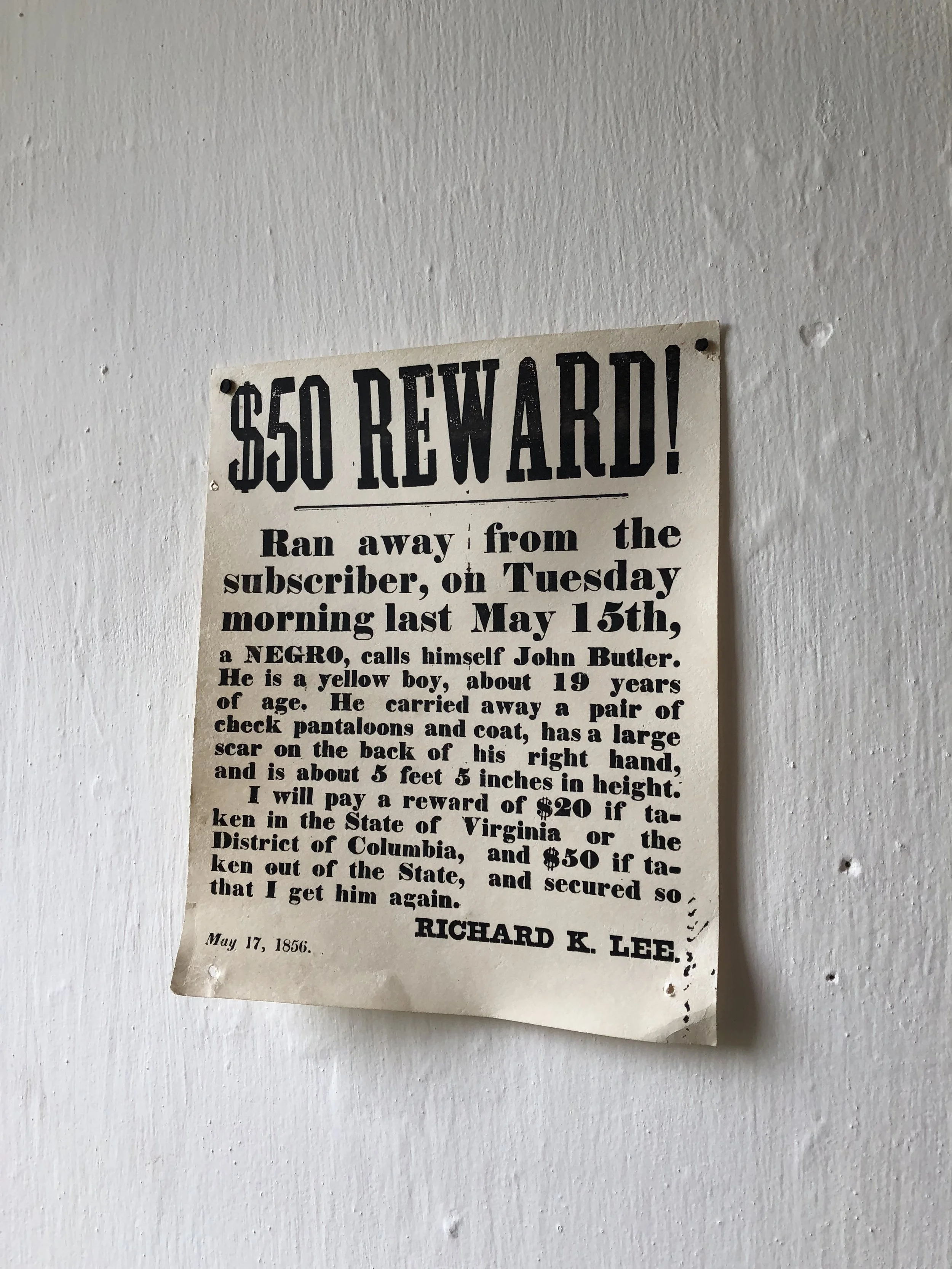

Back to the present. I am finally in a place where some of the most momentous battles and turning points of the war are only a short drive away. I plan to take advantage. I have a vague inclination to go in some kind of order, but I haven’t settled on any particular plan. Two weekends ago we visited the Museum of African American History and immersed ourselves in the misery and pain that is the African-American experience in this country. We grounded ourselves on the bottom floor amidst the anguish of slavery before rising through the levels of the museum until we reached the present day. It was a reminder of why the war was fought and the great abomination it helped to abolish in this country.

This last weekend, we went to Bull Run/Manassas, a ridiculously convenient, 35-minute drive away. I walked the battlefield and examined the guns of both sides along the rolling hills of the valley. Then we walked the Bull Run 1 path**, about 5.5 miles, which visited some of the key points of the first major battle of the war. I saw the Stone Bridge, a key crossing point over Bull Run Creek, which was guarded by the south. The battle begun when the invading Union army came up around the left flank of the southerners. Buggies from Washington rode alongside the Union soldiers on the way to the battle, bringing picnic baskets and blankets to watch the swift defeat of the rebellion. Needless to say, it didn’t turn out that way. The southerners were tough, even though both sides were in reality woefully green.

We walked up Matthews Hill where the south fought tenaciously before getting pushed back by the larger numbers of the Union Army. I felt the heat and humidity in September and thought of the misery of the troops in hot wool uniforms on July 21st. We dipped into the valley and then climbed Henry Hill where the tide of the battle was with the Union forces before southern reinforcements arrived and rallied around Thomas J. Jackson. During a particular tense moment, a commander looked up and said, “There stands Jackson like a stone wall — rally round the Virginians!” TJ Jackson would forever be known as “Stonewall” Jackson after that stand. Today, there is a statue of Jackson near the place where his brigade stood, and next to it someone had planted a confederate flag. In 1861, General Beauregard ordered a counterattack and told his army to shriek like banshees. This was the first iteration of the fearsome “rebel yell.” The Union army broke, and the whole slew of soldiers and picnic-goers fled towards Washington in a chaotic rout called the “great skedaddle.” Nobody thought the war would be easy again. The south celebrated while the tattered union army took months to reform and regain its confidence near Washington, DC.

*I realize now that this was probably highly inappropriate, but it was something that—at the time—made him appear real to me. He was someone in pain, with feelings, instead of a talking head at the front of the lecture hall

**There were two battles fought over the same ground, one in 1861, and one in 1862. Both were Confederate Victories.

Click on the photos below for captions and more info.